-

(818) 833-8737

13521 Hubbard St.Sylmar, CA 91342

- Login

Power lines and wildfires: Experts say communities can be better protected, at a high cost

Posted on 01/18/2025

Power lines and wildfires: Experts say communities can be better protected, at a high cost

OakRidge Mobile Home Park resident watching the Hurst Fire above him and his family shortly after it began on Jan, 7, 2025 10:00pm

Residents in the Los Angeles County community of Sylmar said they once again heard popping noises and a loud explosion. Once again, they saw an orange ball of fire erupt, this time on Jan. 7 below a huge transmission tower at the edge of the Angeles National Forest above them.

“We saw the fire. We saw the flash of light and then heard the boom,” said Emerson Galicia, a resident of the OakRidge Mobile Home Park, northeast of Interstates 5 and 210, recalling the moment before he, his wife and his 3-year-old daughter evacuated that night, as what became the Hurst Fire bore down on them. “When we looked up, we saw half the mountain in flames.”

As California residents grapple for answers in the wake of a massive firestorm event in which two major blazes ravaged parts of Los Angeles — the Palisades Fire and the Eaton Fire —power lines are once again at the center of debate. It's no wonder.

Failed electric equipment and poor maintenance have caused horrific blazes in recent years, sometimes sparked by the smallest of parts, according to government investigators.

There are known measures that can help, experts say, including turning off power when high winds rage in bone-dry vegetation, prepositioning not just fire crews but electric crews at vulnerable substations and lines, and, most costly, burying power lines. Still, the fires keep coming.

The 2023 fire in Maui that killed 102 people was caused by "reenergization" of broken power lines during high winds that showered sparks into dense, dry vegetation.

The 2018 Camp Fire, California's most deadly to date, started after a single worn-out metal hook on a PG&E transmission tower failed, allowing a live line to hit a transmission tower, which created temperatures as high as 10,000 degrees and melted metal wire and tower pieces.

Along with hot sparks, the molten metal fell into drought-stressed trees and grasses, setting them alight.

A history of electric blazes near a huge transmission corridor

Residents in Sylmar have endured similar major wildfires three times in the past 18 years. And each time, the fires tore through transmission towers or old power poles, according to witnesses and formal investigations.

The 2019 Saddle Ridge Fire began in almost the same spot as the Hurst Fire, killing a man and burning 8,800 acres, according to CalFire incident reports. The ignition site was originally identified by LAFD arson investigators as a 50-foot-by-70-foot area beneath a high-voltage transmission tower. A California Public Utilities Commission special investigator concluded SCE had not properly maintained two parts — a Y-shaped insulator fitting and a skyline "jumper wire" that led to a cascading chain of fiery events in which parts of three transmission towers 3 miles apart caught fire.

The 2008 Sayre Fire burned more than 600 homes, including 480 mobile homes, and melted fire hoses. Until this month's fires, it held the record for most structures destroyed in a Los Angeles wildfire. County fire department arson investigators said SCE equipment started the fires, and the utility, while not admitting wrongdoing, said a substation had malfunctioned before it began.

State investigators spent three years trying to pin down if SCE had violated state safety policies with the Sayre blaze. They finally said because SCE told them that no wind tolerance ratings were available for completely burned old power poles, and because they could not pin down accurate wind speeds, the state could not make a definitive conclusion whether the utility's equipment met required safety factors capable of withstanding that day's gusts or not.

This time, though, the Hurst Fire burned less than 800 acres burned and no homes or lives were lost. The fire was 98% contained as of Jan. 15. That's partly due to an immediate, massive firefighting response and well-practiced neighborhood alert systems.

But energy disaster experts say utilities, government agencies and property owners could be doing much more to help protect communities at the edge of flammable wildlands strung with major power pylons. Some measures, though not all, have been implemented in Sylmar, a key transmission corridor for the West Coast. It continuously brings enough live current from Oregon's hydroelectric facilities and central and northern California to power 3 million Los Angeles County homes.

Veteran energy disaster researcher Robert McCullough said if the Hurst Fire had jumped the 210 freeway, millions of people would have been plunged into darkness during howling winds, and undergrounding lines in a risk areas like the Sylmar corridor "absolutely must be done."

The CPUC estimates it would cost $763 billion total to bury all the state's overhead lines. The focus should be on the highest risk areas, McCullough said, which would still not be cheap, but which he said would save lives.

Destruction caused by the Eaton Fire near Altadena, CA - Joe Difazio (USA TODAY)

Power companies and wildfires: An increasingly lethal mix

Not everyone thinks those astronomical costs, which would likely come from customers, are the best approach, though they agree conflagrations caused by power infrastructure are on the rise.

"Most wildfires are not started by utility equipment, but they have started some of the really big ones," said UC Berkeley economist Severin Borenstein, who specializes in energy and public policy. He noted climate change and development of wildfire prone areas have both amped up the odds that a blaze caused by electric equipment can be catastrophic.

"Utilities have been starting fires for 30 years, but they weren't as bad, partially because the vegetation wasn't as dry and partially because there just wasn't as much housing density. Now we’ve populated the urban-wildland interface, and at the same time the vegetation is much drier due to climate change."

More:Ventura County supervisor calls SoCal Edison 'unaccountable, arrogant, unresponsive'

It could be months or years before official causes are determined for the devastating wildfires across Los Angeles County that sparked on Jan. 7 during a severe Santa Ana wind event. But with eyewitness reports of transmission towers catching fire above homes right before the deadly Eaton and the Hurst fires began, state fire investigators are once again hiking to burned transmission tower sites and combing over utility data.

Hurst Fire seen from OakRidge Mobile Home Park (Part 2)

Emerson Galicia, 40 of OakRidge Mobile Home Park in Sylmar taping the hurst Fire wildlife above him and his family shortly after it began on Jan. 17, 2025 after 10:00pm

The California Public Utilities Commission said in a 2020 report that electric utility-related ignitions are "responsible for a disproportionate share of wildfire-related consequences." Southern California Edison agreed in 2021 to pay $550 million in penalties and fines related to the ignition of five wildfires that burned more than 385,000 acres, destroyed thousands of structures, and caused five deaths.

As of Jan. 15, at least 25 people have been killed in LA's Eaton and Palisades fires, according to the Los Angeles Medical Examiner's Office. The wildfires have destroyed or damaged more than 12,000 homes, businesses, and other structures as officials ordered more than 92,000 people to flee their homes. Numerous lawsuits have already been filed against SCE on behalf of people who lost their homes in the Eaton Fire.

SCE has made filings with state regulators, including one for the Eaton Fire "out of an abundance of caution," and said its data showed no problems with area equipment there from 12 hours before the blaze until an hour afterward.

The company said fire agencies are investigating whether SCE equipment was involved in the ignition of the Hurst Fire. The utility said "preliminary information" shows a huge 220 kilovolt circuit experienced a power glitch at 10:11 p.m., and a downed conductor line was discovered at a related transmission tower, "but SCE does not know whether the damage observed occurred before or after the start of the fire." It is unclear whether the tower is the same one Galicia saw catch fire.

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which serves communities impacted by the Palisades Fire, and which co-owns major transmission lines in the Sylmar transmission corridor, is not required as a public agency to file such reports, and declined to respond to questions on possible causes.

"Currently, we are focused entirely on power restoration and response efforts at this time," said Mia Rose-Wong, who works in LADWP's communications and corporate strategy division.

Pull the plug? Debate over planned power shutoffs

One key but often unpopular tool for preventing deadly wildfires is shutting off power when high winds of certain velocities are forecast.

"I'm talking about listening to the National Weather Service and pulling the plug before the lines go down," said McCullough, the Portland, Oregon-based energy disaster consultant with 40 years' experience. He said power lines and other infrastructure have maximum wind thresholds at which they can snap in two, blow out or otherwise be damaged, typically 56 to 58 mph, though newer ones can withstand 80 mph gusts.

"We know where we have transmission and distribution lines mapped out to the start of trees. That is absolutely understood by everyone. When the wind speed gets up, we really need to turn off those neighborhoods.”

In Southern California, that could potentially leave 1.8 million people in high fire risk areas without lights, refrigeration, internet or other essentials, based on a review of SCE and LADWP fire mitigation plans and customer numbers. But McCullough said he was talking about strategically identifying the areas at highest risk.

"We're not talking about, 'Oh my God, let's shut off the lights to LA.' That would be inappropriate," McCullough said.

More than 400,000 people were without power across three Southern California counties for a day or more at the peak of the wildfires, including hundreds of thousands of SCE customers who endured planned service power shutoffs, which are triggered when winds are set to gust high enough and humidity plunges low enough in high fire risk areas.

McCullough also said the utilities should not wait to send crews out after reports of a problem but should pre-position crews at known vulnerable substations and older transmission lines in the known path of predicted high winds.

"Do not just send a truck from headquarters to drive down the street at 30 miles an hour when trying to catch up to a (downed line) that may be happening in winds at 100 miles an hour," he said.

SCE was staging crews at an outdoor location near the Angeles National Forest before a second round of high winds kicked off on Jan. 12, spokesperson Gabriela Ornales said, and had had thousands of workers out checking and repairing lines during the fires.

While SCE and its parent company, Edison International, face the public glare, the county's main power provider and the nation's largest municipal utility, LADWP, has no policy in place to implement planned shutoffs. Instead, the utility relies on what McCullough said is an outdated, "inadequate" wildfire mitigation plan.

"They really haven't evolved their planning at all, even though the science has evolved enormously," he said.

He thinks that's a mistake. Losing electricity can spoil food and create scary traffic scenarios after dark, but compared to "rebuilding your home that burns down," Galicia said, "I think we would take the power loss.”

But cutting power across neighborhoods carries risks, Kurt Cabrera-Miller, president of Sylmar’s neighborhood council, said. He grew up in the city and has lived through fires, earthquakes and power line explosions. He and his husband live in a high-fire severity zone above the 210 Freeway.

Kurt Cabrera-Miller, left, and husband Sheldon Cabrera-Miller at the Santa Monica Pier in January 2023

He said he thinks cutting power in advance could cause chaos. Traffic lights go out already with damaged lines: last week hundreds of evacuating residents in cars and with horse trailers converged at darkened intersections with no emergency personnel to direct traffic. Water is pumped up hillsides here to fill tanks, he said, and if power is cut, he worries about how they'd be refilled.

Downed lines during high winds and power shutoffs may be hard to see, too. Power companies warn people to stay 100 feet away from any broken wire if possible, and to never touch one.

Most critically, cell and internet service can be lost in hilly areas like these, where wireless equipment is often mounted on power poles, leaving residents unable to call 911.

But he said if fire professionals think advance power shutoffs should be done, then they should.

“I’m for whatever helps the firemen; that’s the priority,” he said.

Evacuees from the Eaton Fire dwell among heaps of clothes displayed on the ground at a donation center in Santa Anita Park, Arcadia, CA on January 13, 2025 Etienne Laurent / Getty Images

'Hardening' homes and lines

There are other ways to help stop a massive spread of flames from what start out as smaller power line fires.

After the devastating 2008 Sayre Fire, every possible inch of the homes in Oakridge were rebuilt with fire resistant and fire retardant materials, including home walls, masonry skirting and vents, awnings, fences, porch posts and railings, per a FEMA report. Decomposed granite or rock mulch instead of grass lawns, and cacti and succulents are also recommended for yards, and while Los Angeles County requires brush clearance twice a year, 200 feet back from residential areas, maintenance crews at Oakridge cut back another 25 to 50 feet for extra protection.

Borenstein with UC Berkeley and fire behavior experts say "hardening" your home and eliminating flammable vegetation can help save it when others burn.

"California is kind of a leader ... ever since 2008 we've had some really great building codes that require newly constructed homes in high fire hazard areas to incorporate a set of investments around the roofing materials and the siding and other things that have been shown scientifically to more likely to survive a wildfire," said Judson Boomhower, a UC San Diego assistant professor who studies wildfire risk management.

"They're not going to fully eliminate the risk that the house burns down, especially with these horrible conditions that we saw in Palisades last week, for example. But they are low cost, things that that can make homes more likely to weather these events, or at least give firefighters a fighting chance."

"Hardening" equipment should apply to the big utilities, too, Borenstein and McCullough said.

Edison and other investor-owned utilities are making major progress on installing fire resistant poles, coating live wires in protective material and upgrading equipment to better resist high winds, McCullough said. LADWP has not in his opinion.

The department's current wildfire mitigation report does describe how 100% of vegetation is actively trimmed or otherwise maintained and how pole and other equipment replacements have begun to be done. But it also appears to show just 16 miles of more than 11,200 miles of live power lines overhead have been wrapped in spark-resistant materials. An LADWP spokeswoman did not respond to specific questions about this or other aspects of their plan.

Video Link -

https://www.desertsun.com/videos/news/2025/01/17/could-burying-power-lines-protect-communities-from-wildfires/77787975007/

Is sky high cost of burying live wires worth it?

Sylmar's OakRidge mobile home park does have a significant advantage in fire prevention: Distribution lines to homes were buried underground when it was built in 1979. Undergrounding power lines is the single best method to avoid dangerous arcing of overhead wires, or having dry palm frond hit one that can spark or spread fires, McCullough said.

It's also by far the most costly, Borenstein said, and state utilities data backs that up.

According to SCE, underground conversion is roughly seven times more expensive than covering the conductors and replacing wooden poles with fire resistant poles. It's less expensive to bury lines during new construction, and some jurisdictions' building and fire codes now require it. But bulldozing in existing neighborhoods or public open space and digging new trenches to place lines underground can cost between $3.8 million and $6 million per mile on average, depending on the type of line, according to the Public Utilities Commission.

Crews work to repair downed power lines caused by Hurrican Irma in the 2017 photo in Westt Palm Beach Richard Graulich/Palm Beach Post Files

California has approximately 25,000 miles of big transmission lines, the CPUC says, and about 147,000 miles of smaller, overhead distribution lines powering individual customers. The agency estimates ratepayers would be required to pay $559 billion to convert those 147,000 miles.

Burying a big transmission line costs more — an average of $6 million per mile, and undergrounding the state network could cost $204 billion.

In the U.S., the ordinary person gets stuck with the bills from catastrophic wildfires, said Borenstein and Boomhower, whether as a federal taxpayer covering firefighting and FEMA aid or as a utility customer whose bills have already jumped due to less expensive prevention measures.

There are many low-cost measures that utilities and property owners alike can implement, "the low-hanging fruit," Boomhower said. CalFire has a list that he hopes people will review.

But with firefighting, insurance, health-related and other costs of the two latest major LA wildfires expected to spiral well over $200 billion by some estimates, McCullough insists power lines should be buried, including tearing up portions of popular Southern California national forests. It's already being done in New York state and other places facing power outage risks from storms. The only part of the coastal town of Lahaina that did not burn in the 2023 Maui fire had buried power lines, he said.

"These are hard choices, but they're necessary," he said. The reason is simple: With climate change taking hold, high winds and drought will continue to accelerate.

"The bottom line is, this is not as bad as it's going to get," he said of the Los Angeles fire sieges. "It is going to get worse. Anyone who doubts that is not paying attention."

Janet Wilson is senior environment reporter for The Desert Sun, and co-authors USA Today Climate Point, a weekly newsletter on climate, energy and the environment. She can be reached at [email protected] Michele Chandler contributed to this story.

See you in January

Sign-Up • Receive Agendas

Upcoming Meetings & Events

-

Dec17

Cancelled

Equestrian Committee Meeting - Dec17 Free Produce/Food Distribution at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center 9:30am - 11:30am

- Dec18 FREE MOVIE NIGHT AT THE SNC Council Office

- Dec22 Free Produce/Food Distribution at Olive View/UCLA Medical Center 9:30am - 11:30am

- Dec22 Telescope Nights at Sylmar Library

Sylmar Community Calendar

MyLA311

My LA 311

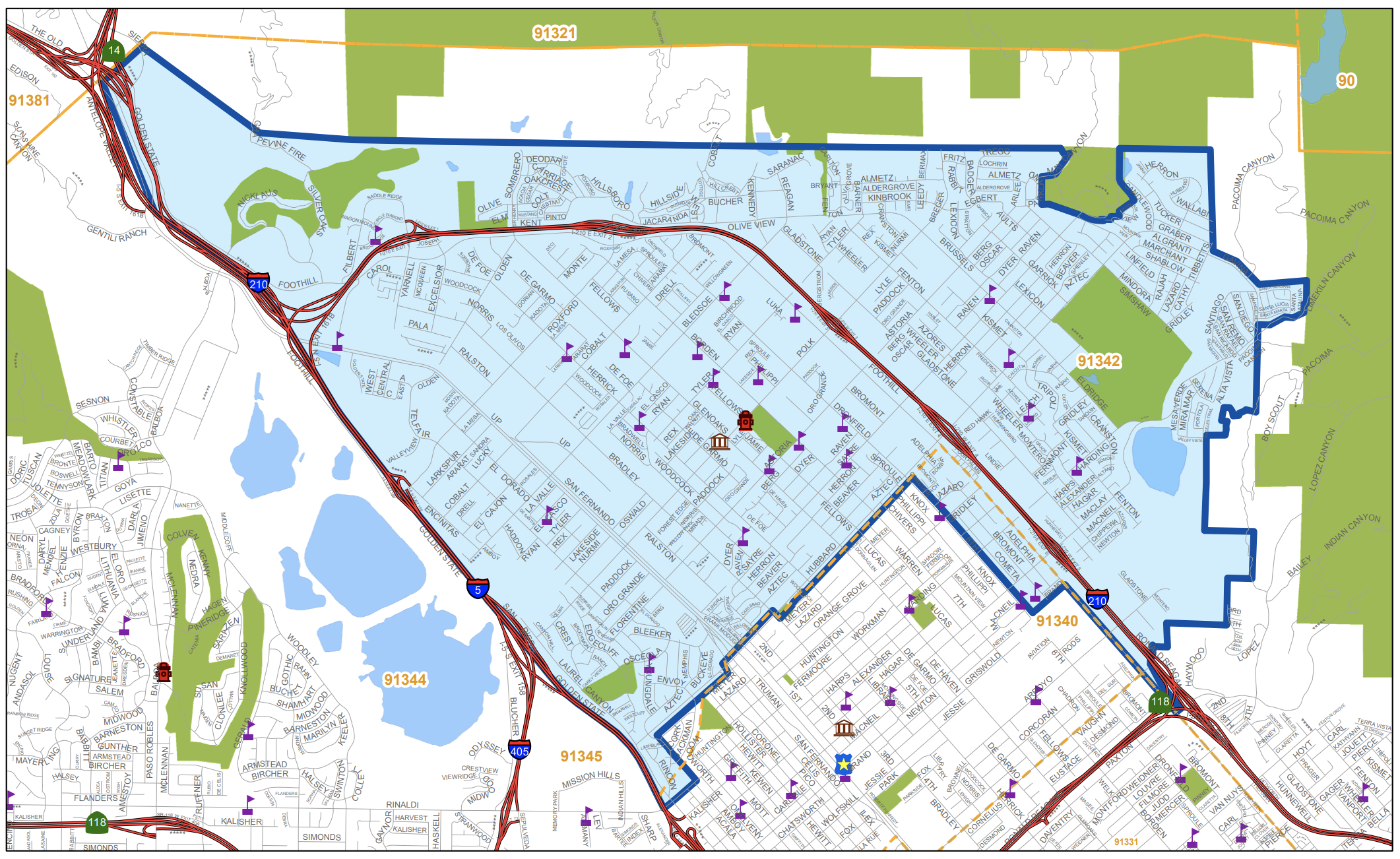

Area Boundaries and Map

View our neighborhood council boundaries for which we deal with.

EMPOWER LA

NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL CALENDAR & EVENTS

The public is invited to attend all meetings.

NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCIL FUNDING SYSTEM DASHBOARD

SUBSCRIBE TO NC MEETING NOTIFICATION